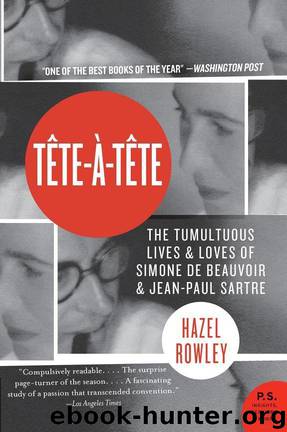

Tete-a-Tete by Hazel Rowley

Author:Hazel Rowley

Language: eng

Format: mobi, epub

Publisher: HarperCollins

Published: 0101-01-01T00:00:00+00:00

NINE

CRYSTAL BLUE EYES

January 1951–December 1954

Sartre had changed, it was true. He had always worked hard, but now, with the help of corydrane, he had turned himself into a work machine. Gone were the evenings he and Beauvoir had once enjoyed at the cinema; gone were their strolls together through Paris. He did not have time.

Corydrane, a stimulant or “upper,” was fairly widely used in the 1950s. But whereas journalists would take a tablet or a half-tablet to get them going, Sartre took four. Most people took them with water; Sartre crunched them. They tasted bad, very bitter, and whether or not it was masochism, Sartre liked to give himself a hard time. On top of the corydrane, he smoked two packets of unfiltered Boyards a day and consumed vast quantities of coffee and tea. In the evening, he drank half a bottle of whiskey, then took four or five sleeping pills to knock himself out.

Increasingly, he felt that writing was a futile, self-indulgent pursuit in a world where children were starving and injustice was everywhere. He no longer read the novels Beauvoir enjoyed; he did not care anymore about fine sentences. He was convinced that politics mattered; literature did not.

He took corydrane to stave off his anxiety about the utter irrelevance of what he was doing. Under the influence of the drug, instead of writhing in anguish, he wrote at white heat. For hours at a stretch he produced page after page, hardly able to keep up with his pen, borne away by a feeling of his own power.

He had temporarily put aside a huge philosophical tome he called Ethics. His essay on Genet, begun as a preface, had grown into a thick book, something between philosophy and literature, a monumental portrait that would leave readers admiring and uncomfortable. (“Who can swallow such a thing?” Cocteau would ask in his journal, noting Sartre’s “will to be the center of attention in literature, and render everything else insipid.”1) He had begun a book on Italy, a country he loved with a passion. His intention, as usual, was to talk about “everything” (history, politics, social problems, the church, art, architecture, and tourism), and was enjoying writing it, but guilt got the better of him. Politics was calling; the project struck him as an indulgence and was permanently shelved. His writing on his favorite cities—Venice, Capri, Rome, and Naples—published posthumously, shows Sartre at his most sensuous and poetic. He spent pages describing the plashing sound gondolas make.2

At the beginning of 1951, he put several projects aside to write a play. His secretary, Jean Cau, observed that Sartre did not seem to enjoy writing plays nearly as much as other things, and that each time he embarked on one, it caused a major trauma in the Sartrean entourage. So why did he do it? He had initially written a part for Olga; these days it was for Wanda. “Others offered jewellery; he offered plays,” writes Cau.3

Wanda loved the stage, and showed genuine talent. She

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Actors & Entertainers | Artists, Architects & Photographers |

| Authors | Composers & Musicians |

| Dancers | Movie Directors |

| Television Performers | Theatre |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31929)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31919)

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26584)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19023)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17394)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15899)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15309)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14041)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13831)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13294)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12356)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8955)

Adultolescence by Gabbie Hanna(8904)

Note to Self by Connor Franta(7659)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(7540)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7305)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(6188)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5395)

Born a Crime by Trevor Noah(5361)